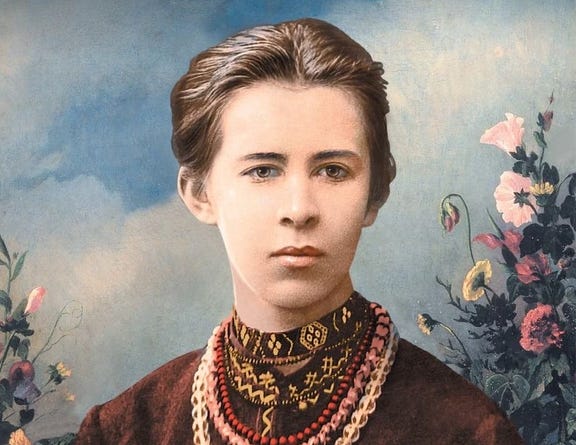

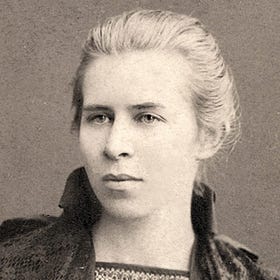

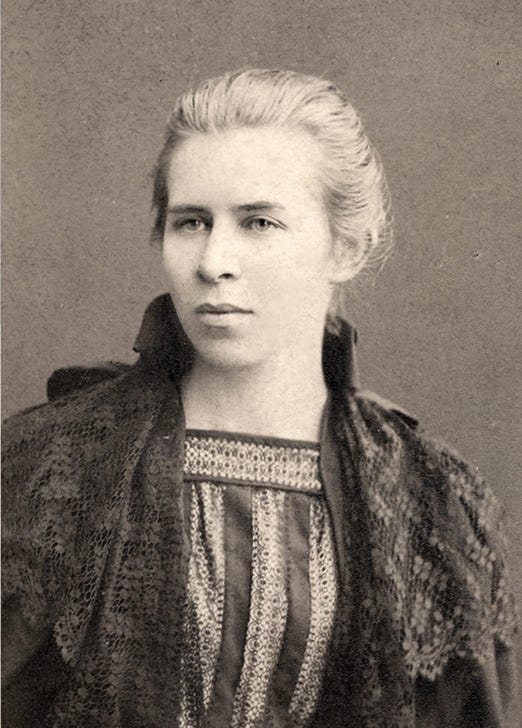

Lesia Ukrainka – the shining star of Ukraine

Pt. 2: The incredible life and work of the most famous Ukrainian writer.

If you like this post, don’t forget to press the like button below! It shows Substack that this article is worth reading and influences if it is recommended to other people. Thank you!

“Those who have not lived through the storm do not know the value of strength.”

– Lesia Ukrainka

Lesia Ukrainka, born Larysa Kosach, was an extraordinarily gifted writer, poet, playwright, translator, intellectual, and feminist of the 19th century. She was a Ukrainian woman who, despite living under the Russian empire’s rule, courageously fought for Ukraine’s independence and future. Nothing could stop her – not oppression, not discrimination, not illness. Despite enormous difficulties and obstacles, she lived boldly and passionately, constantly defying the norms and speaking the truth. She is the most iconic Ukrainian woman writer and is considered to be the mother of Ukrainian literature.

This is the second part of the series about Lesia Ukrainka’s life and work. Read the first part here:

The daughter of Prometheus – Lesia Ukrainka, the legendary Ukrainian writer

She was called the daughter of Prometheus for her words that lit the spark in millions of hearts. The life and work of the most iconic and beloved Ukrainian writer, poet, and activist. Part 1

***

Since childhood, Lesia Ukrainka had been battling tuberculosis. Due to her illness, she had to travel a lot, both to see the best doctors and to spend time in warm climates. During her life, she visited Germany, Austria, Italy, France, Bulgaria, Georgia, Switzerland, and Egypt. Experiencing new cultures and ways of life brought new knowledge and inspiration but, at the same time, deepened Ukrainka’s appreciation of her homeland and its fight for freedom.

In 1891, Lesia Ukrainka came to Vienna for treatment, accompanied by her mother. The trip made a big impression on the young writer and shaped her views of the world and the place of Ukraine in it. The visit happened during the elections in the Imperial Council, the legislature of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Lesia Ukrainka was impressed by the freedom of expression and the right of the people to vote, which was unthinkable in the Russian-controlled Ukraine.

She later wrote to her uncle, Mykhailo Drahomanov:

“The first impression was that if I came to a different world – a better and more free world. It will be so much harder for me to live in my homeland, way harder than it was before. I’m ashamed that we are so unfree, that we are still wearing shackles, and sleeping peacefully in chains. But I woke up, and it weighs heavily on me, hurts, and makes me sad…”

In Vienna, Lesia Ukrainka celebrated her 20th birthday. There, she had a metal fixation device installed on her leg to treat the bones affected by tuberculosis. However, it didn’t prevent her from having an active social life. She and her mother attended museums, theaters, and operas. They had many guests, most of whom were Ukrainian students from Galicia, a region in Western Ukraine that was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire at that time. From conversations with them, Lesia Ukrainka learned that even though Ukrainians had more freedom in Austria than in the Russian empire, they still were the oppressed minority without any rights. She realized that Ukrainians must have their own country and live free from oppression, and this belief became the core of her identity and work.

“I often feel as if I have red spots on my hands and neck from the shackles and yolk of oppression. My hands are chained, but my heart and thoughts are free.”

– Lesia Ukrainka

In the following years, Lesia Ukrainka immersed herself in writing and publishing poetry. Her first poetry collection, On the Wings of Songs, was published in 1892. It contained one of her most famous poems, “Contra Spem Spero!” – Against all hope, I hope.

Contra spem spero! 1890 Translated by Vera Rich Thoughts away, you heavy clouds of autumn! For now springtime comes, agleam with gold! Shall thus in grief and wailing for ill-fortune All the tale of my young years be told? No, I want to smile through tears and weeping., Sing my songs where evil holds its sway, Hopeless, a steadfast hope forever keeping, I want to live! You thoughts of grief, away! On poor sad fallow land unused to tilling I'll sow blossoms, brilliant in hue, I'll sow blossoms where the frost lies, chilling, I'll pour bitter tears on them as due. And those burning tears shall melt, dissolving All that mighty crust of ice away. Maybe blossoms will come up, unfolding Singing springtime too for me, some day. Up the flinty steep and craggy mountain A weighty ponderous boulder I shall raise, And bearing this dread burden, a resounding Song I'll sing, a song of joyous praise. In the long dark ever-viewless night-time Not one instant shall I close my eyes, I'll seek ever for the star to guide me, She that reigns bright mistress of dark skies. Yes, I'll smile, indeed, through tears and weeping Sing my songs where evil holds its sway, Hopeless, a steadfast hope forever keeping, I shall live! You thoughts of grief, away!

The first collection of poems was followed by the second, Thoughts and Dreams, in 1899. Both of the books were published in Lviv, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Despite the danger, they were secretly smuggled to Kyiv, where the Russian tsar’s order strictly forbade books in Ukrainian. Ukrainian theater and musical performances were also banned. It looked as if Ukrainian culture was completely suppressed, but in reality, it was kept alive by people like Lesia Ukrainka.

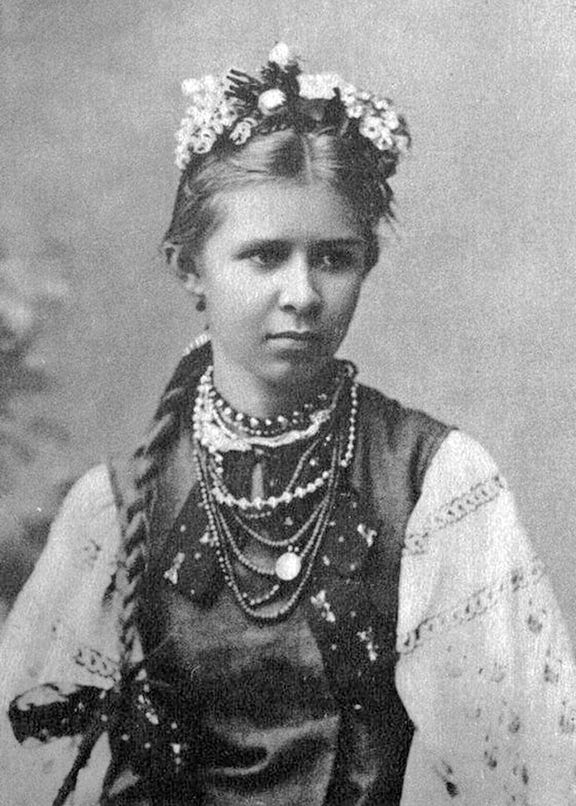

Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska, the daughter of the writer and playwright Mykhailo Starytsky, wrote about the day when Lesia Ukrainka presented her first published book for the first time during a secret meeting in their house:

“I remember the day when Lesia, at that time a very young, slender and tall, in Ukrainian attire, came to see us with her book. This was a general celebration. My father put on his pince-nez, picked up the paper knife, gently patted the greyish-blue volume as if it were a child, and began to cut the pages carefully. This was not the feeling with which we now pick up a new Ukrainian book – this was a feeling of special joy: this book which had travelled from abroad in such great danger – either in an envelope or deep in someone’s pocket – lay now in front of us, new and fresh, like a message about the possible fate of the Ukrainian language, about some far away future life.”

Lesia Ukrainka’s second poetry collection included a poem about Robert the Bruce and his fight for Scotland’s freedom. She dedicated this poem to her uncle, Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was forced into exile for his activism for Ukraine’s independence. As in all her works about the struggle for freedom in different historical periods, Lesia Ukrainka always wrote about Ukraine and Ukrainians.

After reading Lesia Ukrainka’s second poetry book, Ivan Franko, a famous Ukrainian writer and literature critic, wrote in his review in 1899:

“One cannot resist the feeling that this fragile, invalid girl is almost the only man in all our present-day Ukraine.”

Despite being portrayed as “a fragile, invalid girl”, Lesia Ukrainka never let the illness define and limit her. There was nothing in the world that could do it. She continued writing poems and articles, translating foreign authors into Ukrainian, and maintaining social activism.

***

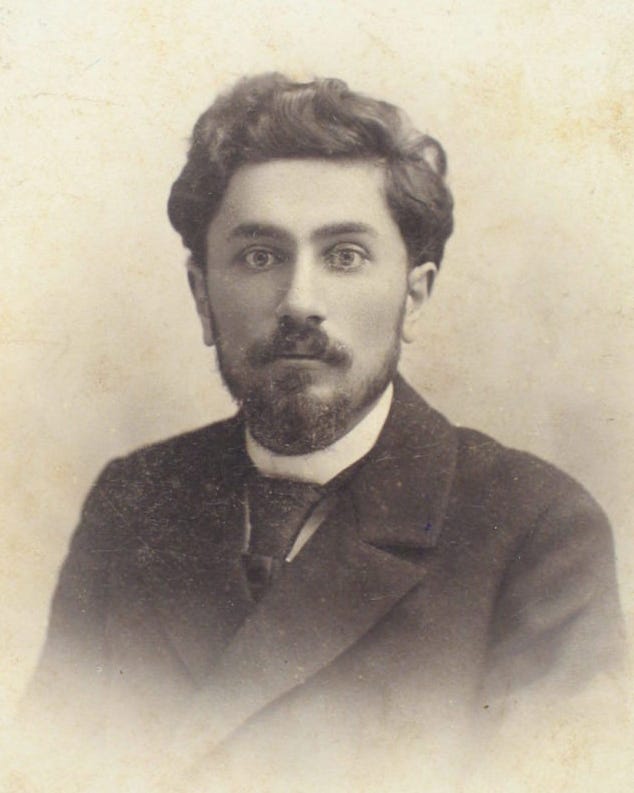

Ukrainka spent almost every summer in Crimea, as its warm, dry climate was prescribed by the doctors. There, she met a Belarusian revolutionary, Sergei Merzhynskyi, who was also undergoing treatment for tuberculosis. Lesia Ukrainka fell in love. Unfortunately, her feelings weren’t mutual, but the young people developed a close friendship.

In 1900, Lesia Ukrainka wrote a poem, Ivy.

I'd like to wind around you, strong and tight, Like ivy vine, to shield you from the world. I promise I won't take away your life, My leaves will cover gently rocky walls. The vine brings life and wraps the bare wall, It guards it from the storm that rages high. Yet ruin holds the vine so it won't fall, A steadfast bond that neither can deny. They're good together, just like you and me, But when the ruin crumbles, starts to fall, Let it conceal the vine beneath debris, There is no point in living all alone. It will be lying wounded, ragged, and weak. Thrown to the ground by ruthless fate, Or, it will hang on a poplar tree, And will become much worse than death for it. - My adaptation of the translation by Olesya Redko.

Sergei Merzhynskyi visited Lesia Ukrainka several times in Ukraine, but when his health deteriorated, she decided to come see him in Minsk. It was a huge scandal for an unmarried woman to stay with a man in one house, and Ukrainka’s mother strictly forbade her to even think about it. However, Lesia Ukrainka didn’t need anyone’s permission to follow her heart. Despite severe objections from her family, she came to Minsk and stayed with her friend for two months, until his death.

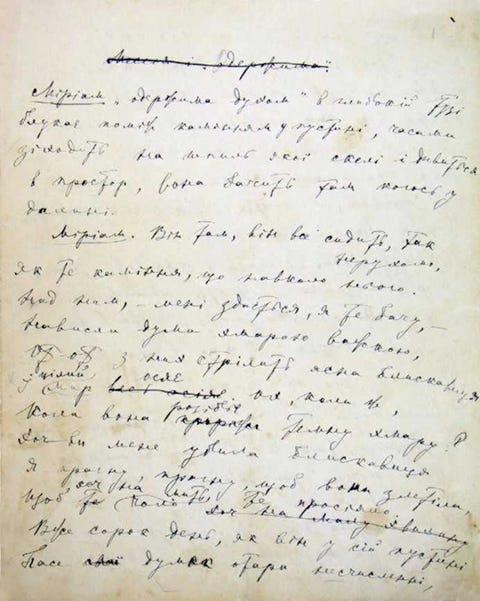

On the night of Merzhynskyi’s death, Lesia Ukrainka wrote a dramatic poem, Possessed. It became one of her most powerful works and the beginning of writing drama. The poetic play features a Biblical narrative about Miriam, a prophetess, and the Messiah. It shows the events of Jesus’s 40 days in the desert, his teachings, the prayer at Gethsemane, his crucifixion and resurrection – all from the perspective of Miriam, a woman who loved him more than anything and didn’t want him to suffer for the sins of others. The poem gives voice to the woman who had never been given it before and shows her strength, passion, and sacrifice.

Read a translated excerpt of the poem here

Lesia Ukrainka remembered the night she wrote the poem in the letter to Ivan Franko:

"I wrote it on such a night that I would probably live for a long time if I managed to survive it. If someone asked me how I stayed alive that night, I would say, "J'en ai fait un drame…" [I made a drama out of it]

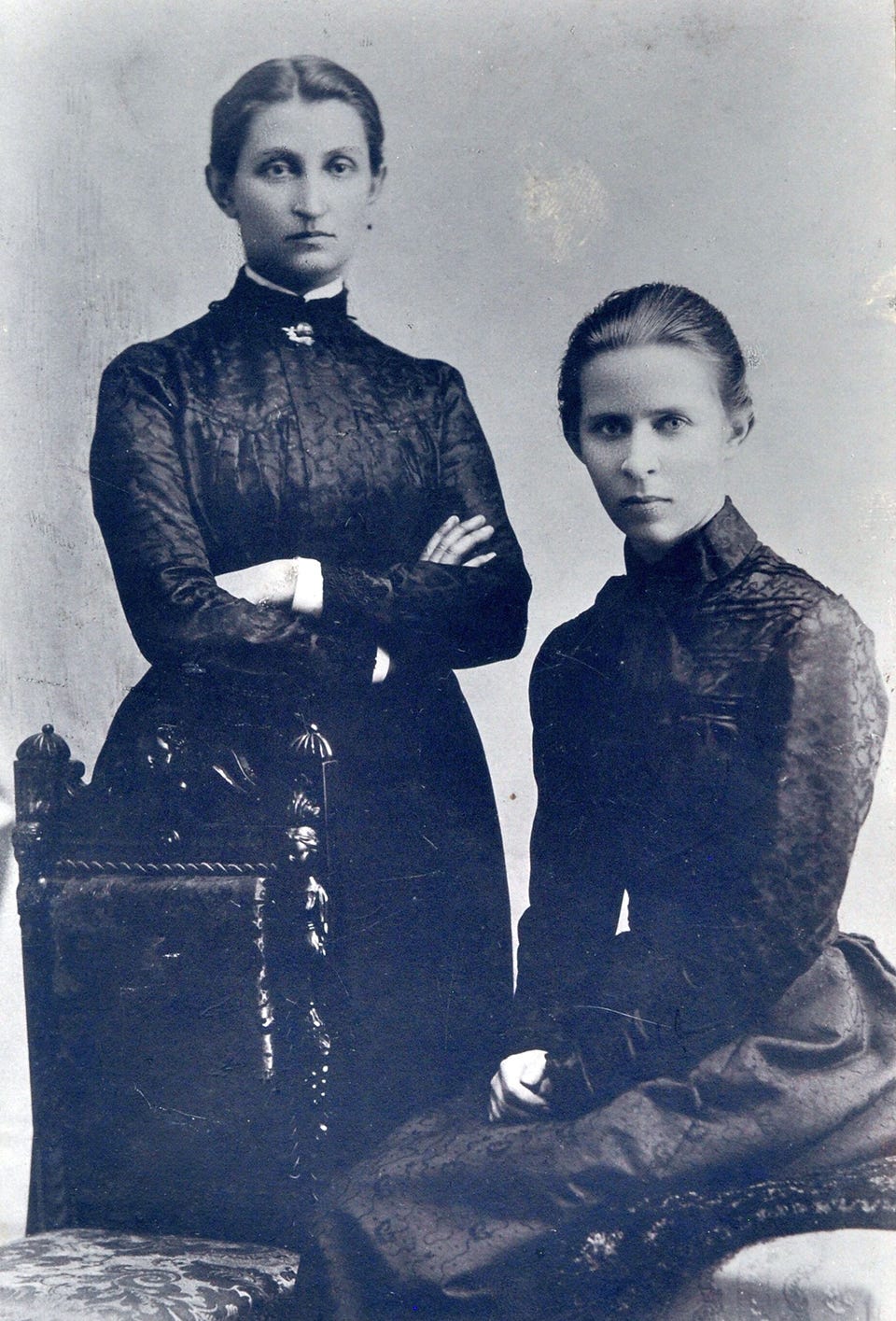

The death of Sergei Merzhynskyi was one of the most shocking and hard moments in Lesia Ukrainka’s life. Grieving and in a state of deep sorrow, she came to visit her close friend, a prominent writer and feminist, Olha Kobylianska, in Chernivtsi. The days spent in nature, walks in the mountains, and her friend's support helped Lesia Ukrainka recover from a deep emotional shock and get back to writing. There, in Chernivtsi, she published her third poetry collection, Echos.

After all, love is like water. It carries us, spins, plays, rips, gently strokes, caresses, and drowns. Where there is heat, it boils, but when it encounters cold, it turns into ice.

– Lesia Ukrainka

Lesia Ukrainka had a faithful suitor, Klyment Kvitka, a young lawyer and talented ethnomusicologist, who was deeply in love with her and tried to get her attention for many years. Gradually, he won her affection, and in 1903, Ukrainka came to live with him in Tbilisi, Georgia. It was revolutionary at that time for a couple to live together without being officially married, but Lesia Ukrainka defined the norms all her life. One of the reasons she didn’t want to marry officially was because during the marriage ceremony at church, a woman had to say that she would obey and serve her husband. It contradicted the values of Lesia Ukrainka, who strived for equality and independence all her life. However, she was forced to eventually marry Kvitka under huge pressure from her family in 1907. In letters to her friend Olha Kobylianska, she recalled the marriage as very calm and happy.

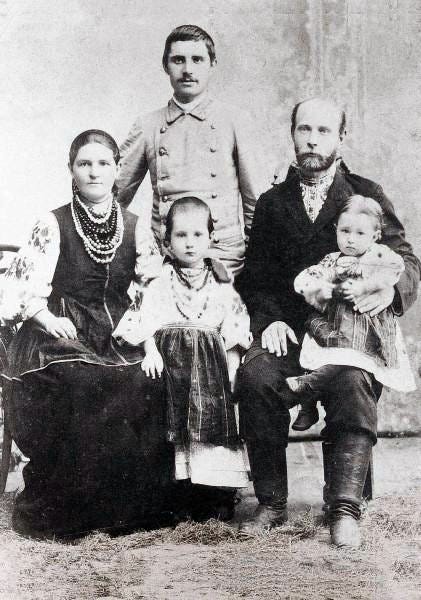

In 1908, together with her husband, Lesia Ukrainka sponsored an ethnographic expedition of the ethnographer and composer Filaret Kolessa to record and preserve the traditional songs of the Ukrainian bards, kobzars, who were usually blind and played kobza and lira. The songs that dated many centuries back had never been recorded before, and Lesia Ukrainka understood the urgency and importance of preserving them. Thanks to her, the songs were recorded using a phonograph, and we now have an opportunity to listen to them. In 1931, the Soviet authorities invited all Ukrainian kobzars to attend a congress in Kharkiv. Those who arrived were taken out of the city and executed.

You can listen to the unique recordings made during the expedition here:

Recordings of the Ukrainian kobzar's songs

Lesia Ukrainka made many recordings herself, where she sang traditional Ukrainian songs. There is only one left where we can hear her voice:

***

Before 1905, the works of Leisa Ukrainka were published abroad and smuggled into Kyiv. Each book had only a few copies and was passed from one person to another. Many people made handwritten copies of Ukrainka’s books. However, in 1905, the Tsar’s order that banned the use of the Ukrainian language in print was lifted. Lesia Ukrainka’s works were freely published in Ukraine for the first time, and they immediately had great success.

During her life, Lesia Ukrainka wrote more than 20 dramatic poems. One of them is Cassandra, written in 1907, which tells the story of the Trojan War. However, it is told from a woman's perspective, the Trojan princess Cassandra. The god Apollo granted Cassandra the gift of prophecy, but when she rejected his romantic advances, he cursed her to see the future but never to be believed. In an absolutely unprecedented approach, Lesia Ukrainka tells the story of the legendary war from a woman's viewpoint. It is a story about colonialism and oppression, about patriarchy and women’s roles in society. Cassandra is an autobiographical work, and, as the majority of Ukrainka’s writing, carries parallels to Ukraine.

Buy the book with the latest translation (published in 2024)

The book Lesya Ukrainka: Life and Work. Selected Works by Constantine Bida and Vera Rich, published in 1968, that contains the poem can be found here and here.

In 1912, Lesia Ukrainka wrote a dramatic poem, The Stone Host, which was the first time the story about Don Juan was written by a woman.

A year earlier, the fairytale drama The Forest Song was published, which is considered to be one of Lesia Ukrainka’s best works. It is a play in three acts that tells a story about a forest nymph from Ukrainian folklore, Mavka, who falls in love with a peasant boy, Lukash. The boy has a unique gift for music, as when he plays, the whole forest comes to life, and his music awakens Mavka’s soul. It is a story about love and betrayal, the fight between good and evil, and how the power of a woman’s love can overcome any obstacles and achieve the impossible. Lesia Ukrainka once again gives her female characters agency and the power to choose their own destiny. The play features beautiful Ukrainian landscapes written from Ukrainka’s childhood memories and fascinating Ukrainian mythology and folklore. It’s one of Ukraine's most popular theater performances and has been adapted for ballet, opera, and an animation movie.

Read the translated excerpts here and here

The book with the newest translation is coming this year; get on the list to be notified

The book The Spirit of Flame. A collection of the Works by Lesya Ukrainka by Percival Cundy and Clarence A. Manning published in 1950 that contains the poem can be found here.

Since 1910, the health of Lesia Ukrainka significantly deteriorated. Yet, during her last years and unbearable pain, she wrote her most important works.

Lesia Ukrainka died on August 1st, 1913, in Georgia, surrounded by her husband, mother, and sister. She was only 42 years old. Her body was transferred from Georgia to Kyiv. So many people attended the funeral that the Russian authorities patrolled it on horses and forbade people to give speeches as they were afraid that it would turn into a pro-Ukrainian protest. The casket with Lesia Ukrainka’s body was carried by six women, her friends, which was very unusual, as the caskets were carried by men. It was a testament to Lesia Ukrainka’s fight for women’s rights and equality.

Lesia Ukrainka left a powerful legacy, and her words continue to inspire, resonate, and bring hope more than a century after her death. The quote of Lesia Ukrainka, “Whoever liberates themselves, shall be free,” became the motto of the EuroMaidan revolution in 2014, when Ukrainian people, once again, fought for their freedom from Russian rule and oppression. In the year 2025, the fight continues.

Ah, for my body do not grieve! It’s now shining with fire and gold, As good wine, it’s clear and strong, Dancing sparks fly high, bright and free. Light and airy pinch of dust Will return and rest in the ground below, By the water, a willow will grow – My end will become the beginning of life. From the poetic drama “The Forest Song,” 1911 Translated by Darya Zorka

Email: daryazorka@substack.com

Shop my art on Etsy

Watch the “20 Days in Mariupol” documentary

Watch Frontline PBS documentaries on Ukraine

Donate to help Ukraine: UKRAINE DONATION GUIDE

Gift a subscription to From My Heart ♥︎

Six women carried her coffin - I found that so intensely moving and so powerful. Great to hear her voice too. What an inspirational woman - thank you for telling us her story Darya.

"I’m ashamed that we are so unfree, that we are still wearing shackles, and sleeping peacefully in chains."

What a great line and how apt for so much of what is going on in the world today. When I read some of her poetry I was reminded of some of John Keats poems which I have not read for decades but which have some of that same melancholy beauty to them. Different eras different sex but a very very talented woman.