The daughter of Prometheus – Lesia Ukrainka, the legendary Ukrainian writer

Pt.1: The life and work of the most iconic and beloved Ukrainian writer, poet, and activist.

If you like this post, don’t forget to press the like button below! It shows Substack that this article is worth reading and influences if it is recommended to other people. Thank you!

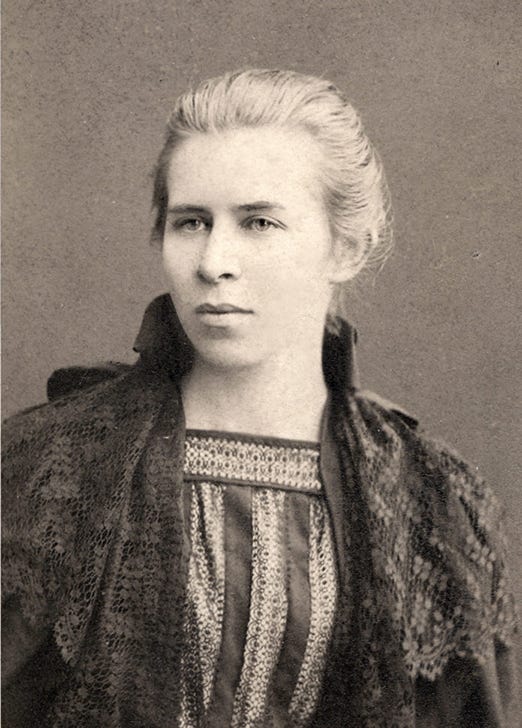

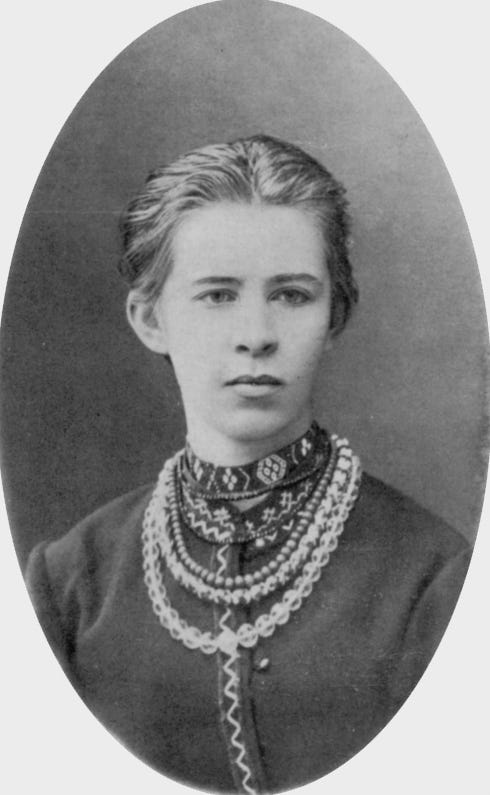

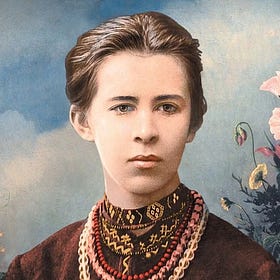

She was called the daughter of Prometheus for her words that lit the spark in millions of hearts. Lesia Ukrainka, born Larysa Kosach, was an extraordinarily gifted writer, poet, playwright, translator, intellectual, and feminist of the 19th century. She spoke ten languages and could freely read and write in all of them. She translated the works of Homer, Hugo, Byron, Heine, Shakespeare, Dante Alighieri, and other famous writers into Ukrainian. She wrote more than 250 poems, 22 dramatic works, and numerous prose pieces. She defiantly published in Ukrainian while the use of Ukrainian in print was forbidden by the Ems Ukaz of the Russian Tsar.

Lesia Ukrainka’s work was inspired by classical Greek, Roman, and Bible stories, as well as works of European writers and philosophers, but always had a deep connection to Ukraine and its culture. Her ideas of gender equality were revolutionary and shocking at the time she lived, and in her works, she gave voice and agency to the women who were never given it before. Yet, during her life and a long time after her death, Russians who controlled and subjugated Ukraine portrayed Lesia Ukrainka as a weak woman who wrote folklore and children’s stories, afraid of her power and influence. Despite all attempts to belittle her talent, she became the most legendary, inspiring, and influential woman writer in Ukrainian history.

“My only weapon is the word, But there’s no reason both of us should die! Perhaps in the hands of some unknown brothers My word will become an even better sword Against those who condemn us to death.” – Lesia Ukrainka

***

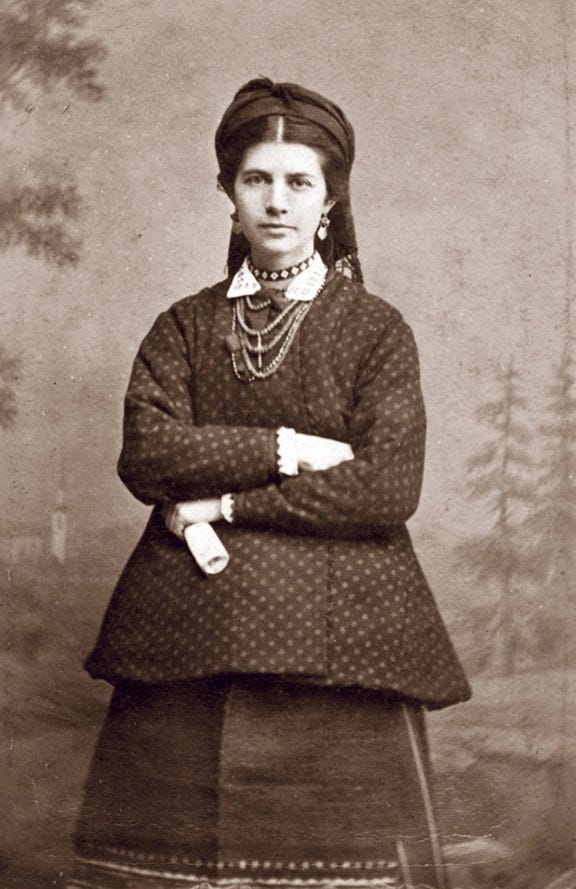

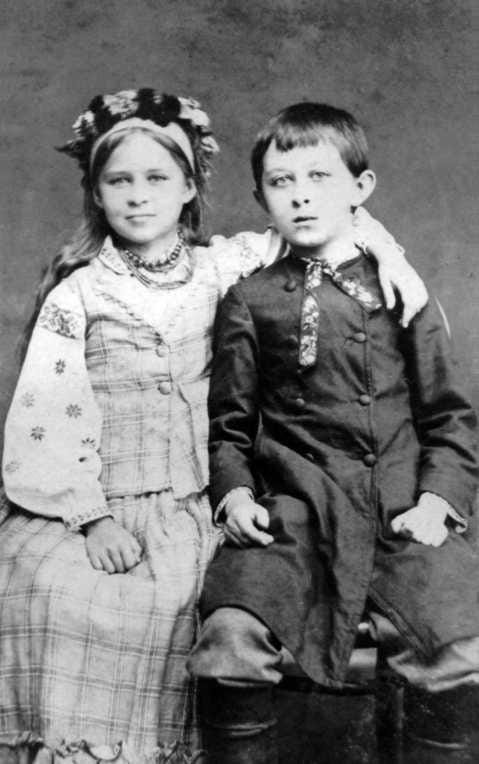

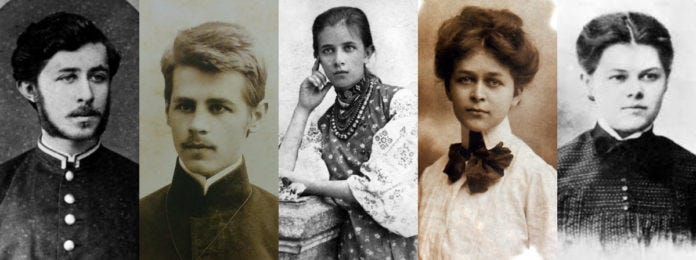

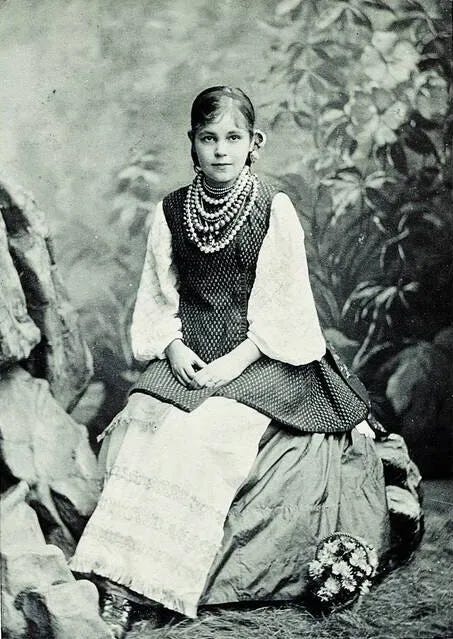

Larysa Kosach, who would become known to the world as Lesia Ukrainka, was born on February 25, 1871, in a wealthy Ukrainian family in Novohrad-Volynskyi (now Zviahel), Ukraine, which was under the Russian empire’s rule at that time. Her mother, Olha Drahomanova, known under the literary pseudonym Olena Pchilka, came from a noble family and was a famous writer, ethnographer, philanthropist, feminist, and civil activist. Her father, Petro Kosach, was a lawyer and a descendant of a noble Cossack family and held high-ranking government positions. He contributed large sums to fund Ukrainian scholars and publications in the Ukrainian language. The family had six children. Lesia Ukrainka was the second child. When her mother fell ill after her birth and was advised to go abroad for treatment, her father took a leave from work. He cared for a newborn Lesia and 2-year-old son Mykhailo for six months, and probably became the first man in Ukraine to take a parental leave.

Lesia Ukrainka had a very close relationship with her father, and they had many characteristics in common. As Lesia's sister Olha wrote:

“They were both similarly gentle and very kind; but both were capable of great and sudden anger when deeply aroused by something particularly annoying. Both were highly principled persons: they could be very indulgent to their loved ones or favourite pursuits, but I cannot imagine anything at all which could force Father or Lesia to do something which they considered not right or dishonorable.

Father and Lesia had one especially precious characteristic in common: they placed a very high value on human dignity in every person, even the smallest child, and always behaved in such a way, so as not to offend or disregard this dignity.”

The Kosach family was one of a few noble families who spoke Ukrainian, as all the rest were Russified after Ukraine fell under the Russian empire’s rule. They were the members of Stara Hromada, the secret Ukrainian society that was the center of cultural life in Ukraine and the Ukrainian national movement. The Ukrainian-speaking elite were in close contact with each other, and Lesia grew up surrounded by highly educated, creative people who remembered and valued their culture and identity. Among them were the family of composer Mykola Lysenko and writer and playwright Mykhailo Starytsky.

Lesia Ukrainka and all her siblings received education at home from private tutors and their mother, as their parents wanted to give them education in Ukrainian. It was only possible at home, as every educational institute in Ukraine was teaching students in Russian. Olha Drahomanova wanted to give her children the best education possible, and she translated foreign authors into Ukrainian, which inspired Lesia and her older brother to do the same. The children learned multiple languages, mathematics, history, philosophy, and other subjects. Lesia’s mother collected Ukrainian embroidery and folk art and sang Ukrainian folk songs daily, which immersed her children in Ukrainian culture from their first days.

As the close friend of Lesia Ukrainka, Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska, wrote:

“We were the first generation of Ukrainian children who became conscious Ukrainians not from naturally growing up in the Ukrainian villages and surrounded by their culture, but being the city kids whose parents raised them to be Ukrainians in the hostile environment, despite everything.”

Lesia Ukrainka learned to read when she was four years old. By six, she was playing piano and embroidering. She loved to dance and sing and had an exceptional talent for music, dreaming of becoming a musician.

When she was nine, she wrote her first poem, Hope. It was dedicated to her aunt, Olena Kosach, a Ukrainian writer and revolutionary, who was arrested and sent to a prison camp in Siberia, which came as a huge shock to little Lesia.

Hope 1880 I have no happiness, and I am not free, There’s only one hope left for me: To return to Ukraine once again, And see my native land in the end, Have another look at the blue Dnipro – No matter if I live or die there alone; Have one more look at the steppe and graves, Let one last passionate reverie rave… I have no happiness, and I am not free, There’s only one hope left for me.

When Lesia Ukrainka was ten years old, she went to the river during a winter celebration and got her feet very cold. She fell seriously sick afterwards, and two years later, she was diagnosed with bone tuberculosis. She fought with this illness for the rest of her life and called it “the thirty-year war.” Tuberculosis affected her legs and wrists and prevented her from playing piano she loved so much. Lesia was forced to spend months in bed with both her arms and one foot in casts. Once, her aunt noticed that the little girl, while lying in bed, was beating rhythmically with her one free foot. When the aunt asked what she was doing, Lesia quietly answered, “I’m playing piano.”

Unable to play, Lesia poured her energy into reading and writing, which unleashed her imagination and literary talent. However, all her relatives said that she would have become a genius composer if not for the illness.

Lesia Ukrainka was very close to her uncle, Mykhailo Drahomanov, who became her mentor and teacher. He was a professor, scientist, economist, philosopher, and ethnographer who was forced to flee Ukraine because of his liberal European and pro-Ukrainian views and political activism. They corresponded with Lesia in letters for 18 years. Drahomanov supervised her reading, recommended the scientific and literary works of Western European writers, and sent her many of his works as well. He deeply influenced and encouraged Lesia to develop her independent thinking and writing style.

When Lesia Ukrainka was 13 years old, her poems were published in the Ukrainian magazine Zorya in Lviv. The Ukrainian town was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and publications in Ukrainian were allowed there, unlike in the Russian-controlled Ukraine.

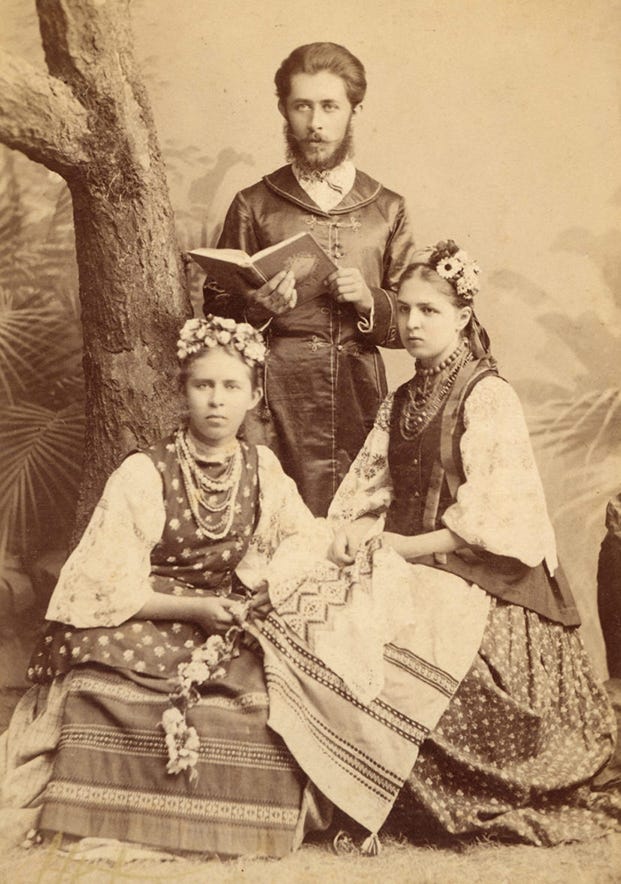

At the age of 17, Lesia and her brother Mykhailo decided to make a series of translations of popular foreign and classic authors into Ukrainian. Their friend Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska joined them. At that moment, it’s been 12 years since the start of the Tsar’s order that forbade publishing in Ukrainian, but it didn’t stop the young people. They had an ambitious goal of translating dozens of books to introduce Western literature to Ukrainians, and they needed more people who could help with translations. That’s how the literature club “Pleiada” was born. They met at various homes and held literature discussions and contests. As a result, they prepared three collections of translations for publication, but all of them were banned.

Liudmyla Starytska-Cherniakhivska described Pleiada meetings:

“This was a meeting of friends who cared for writing and the spirit of Ukrainian life. One and all felt a great solidarity of interests and social responsibility. They read their works, discussed both content and form, and dreamed about a Ukrainian press, a Ukrainian language, schools, Ukrainian life. But the dreams always seemed so elusive…Yet, they wanted to realize them, if only in the smallest detail.”

When Lesia was 19 years old, she wrote a textbook named The Ancient History of Eastern Peoples for her younger sister Olha. The book contained more than 250 pages and included the history and literature of ancient Egypt, India, Persia, Babylon, Assyria, Media, Israel, and Phoenicia. Lesia did all the research and translations herself, with some help and guidance from her uncle. Olha published the book 28 years later, in 1918.

In 1892, when Lesia Ukrainka was 21, her first poetry collection, On the Wings of Songs, was published in Lviv and smuggled into Kyiv. The career of the young writer and poet had just begun.

Read the second part here:

Lesia Ukrainka – the shining star of Ukraine

The incredible life and work of the most famous Ukrainian writer. Part 2

Email: daryazorka@substack.com

Shop my art on Etsy

Watch the “20 Days in Mariupol” documentary

Watch Frontline PBS documentaries on Ukraine

Donate to help Ukraine: UKRAINE DONATION GUIDE

Gift a subscription to From My Heart ♥︎

I really enjoyed learning about this extraordinary woman. Thank you. Looking forward to part two.

Thank you for sharing her amazing story! ❤️