The incredible story of Shchedryk – a Ukrainian song behind the beloved Carol of the Bells

The forgotten history of the most famous Christmas song and how the power of music changed the world’s perception of Ukraine.

If you like this post, don’t forget to press the like button below! It shows Substack that this article is worth reading and influences if it is recommended to other people. Thank you!

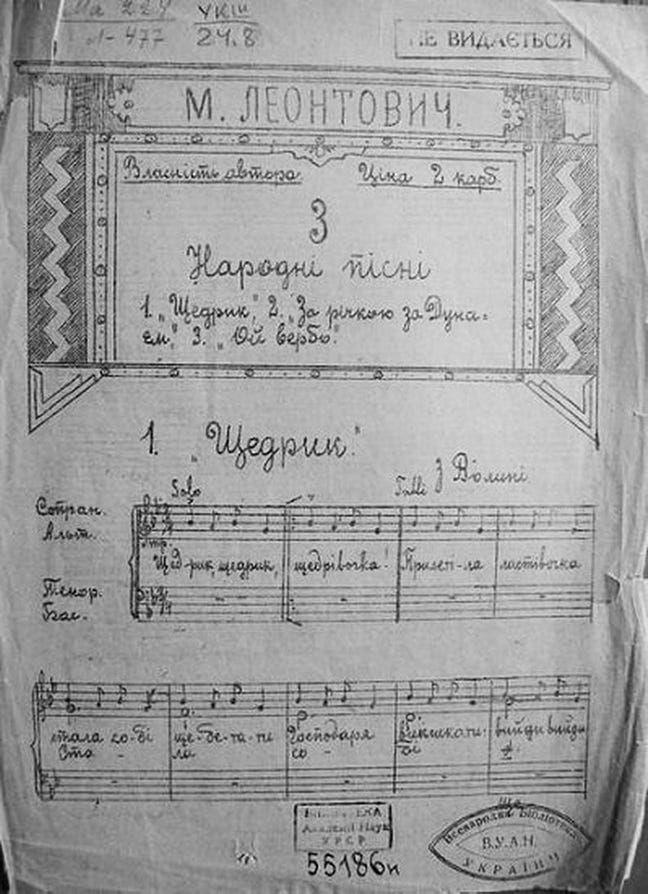

Yesterday, December 13th, was the birthday of Mykola Leontovych – a genius Ukrainian composer born almost 150 years ago who gave the world the favorite Christmas song, “Shchedryk,” which was adapted in English as “Carol of the Bells.” The original Ukrainian song is not about Christmas, but a New Year’s Eve, where a swallow flies into a house and wishes the family a happy and plentiful year ahead. Shchedryk comes from the word that means generosity in Ukrainian. On New Year’s Eve, people in Ukraine come from house to house and sing carols called shchedrivky. Leontovych took inspiration from an ancient Ukrainian folk song, which historians date back to pre-Christian times.

The lyrics: Shchedryk, shchedryk, a shchedrivka Here flew the swallow from afar Started to sing lively and loud Asking the master to come out Come here, oh come, master — it’s time In the sheepfold wonders to find Your lovely sheep have given birth To little lambs of great worth. All of your wares are very fine Coin you will have in a big pile All of your wares are very fine Coin you will have in a big pile If not money, then chaff: You have a dark-eyebrowed [beautiful] wife. Shchedryk, shchedryk, a shchedrivka Here flew the swallow from afar

***

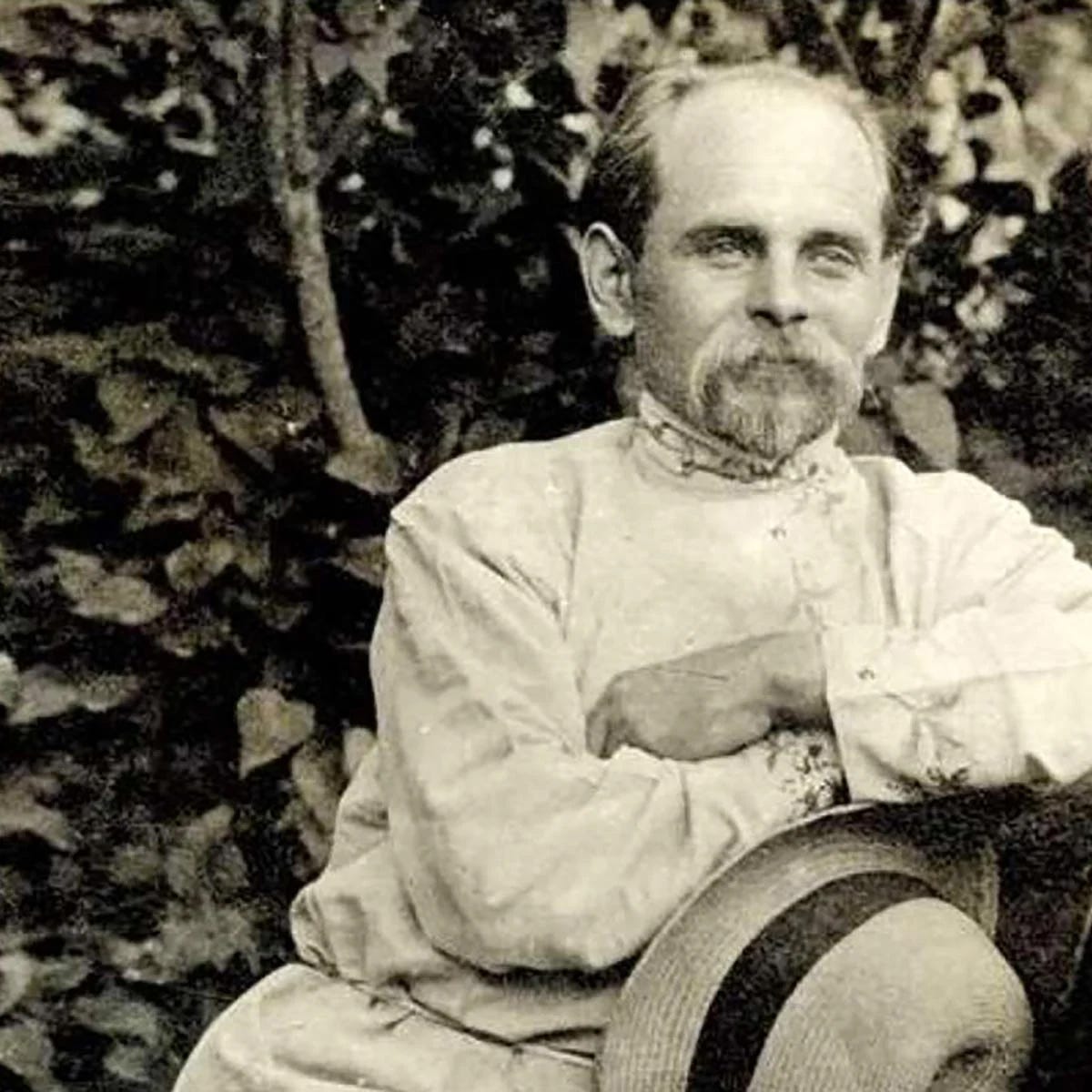

Mykola Leontovych was born in a village in the Podilla region of Ukraine in 1877. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were priests. Leontovych grew up surrounded by music since early childhood. His parents played multiple musical instruments. Father curated a church choir, and mother adored Ukrainian folk songs and frequently sang them at home. Leontovych finished a theological seminary and started his career as a music and mathematics teacher at a village school. People had always spoken of him as a quiet and shy person. He worked in multiple schools and colleges, and in 1904, he moved to Pokrovsk, a town in the Donetsk region, to teach at the railway school. There, Leontovych wrote Shchedryk – the song known worldwide as Carol of the Bells.

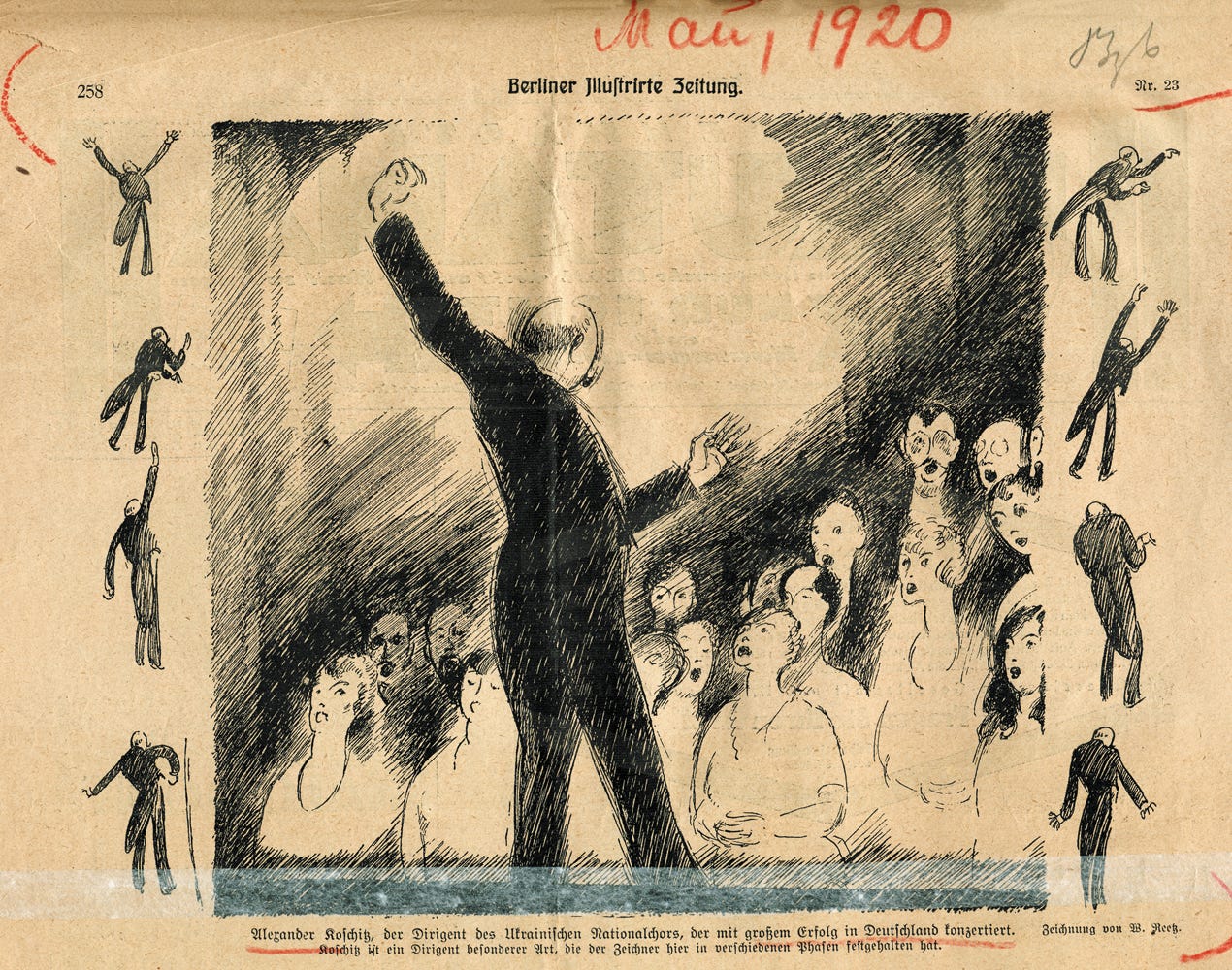

Leontovych spent 20 years working on Shchedryk, constantly revising it, and always critical of his work. The song was first performed in Kyiv in 1916 under the direction of Ukrainian conductor Oleksandr Koshyts, who encouraged and supported Leontovych over the years of the song's creation. Koshyts is considered to be the Godfather of Shchedryk, and he was the one who introduced it to the world.

After the revolution of 1917, the Russian empire collapsed, and the Ukrainian People’s Republic was formed. Finally, the chains of Russian oppression fell, and people could perform Ukrainian songs and celebrate Ukrainian culture without fear of prosecution. Mykola Leontivych moved to Kyiv and started to work as a conductor and composer at the Kyiv Conservatory. During his life, he wrote more than 150 choral compositions and collected hundreds of Ukrainian folk songs from his native region. Despite having an immense talent recognized by everyone around him, Leontovych considered his work mediocre. It is known that he destroyed many of his compositions, and when he published a book with the folk songs he collected, he bought back all the copies the next day.

***

Months after the revolution, Russian Bolsheviks (communists) who came to power occupied the East of Ukraine, claiming that it was “a liberation” and framed their invasion as an internal Ukrainian conflict. Ukraine asked the world for help, but the idea of Ukraine’s independence wasn’t supported at all. The Russian elite who fled to the West after the revolution received sympathy and successfully promoted Russian imperial interests. They presented Ukrainians as “Malorussians” without distinct culture and history, and people believed them. The fight for power in Russia intensified. The White Tsarist Army wanted to restore the Russian empire, and the Red Bolsheviks Army wanted to build communism, but neither of them wanted Ukraine to regain independence. At some point, France sent soldiers to Ukraine, where they helped imperialist Russians fight the communist Russians, but in reality, all they did was help Russians occupy Ukraine.

It was 1919, Ukraine was bleeding on the frontline, outnumbered and unequipped but desperately fighting for freedom. The world was supporting Russian imperialist ambitions and admiring Russian culture. At that time, Ukrainian state commander Symon Petliura visited a concert in Kyiv where he heard a composition, “Legend” by Mykola Leontovych. He was so impressed that he came up with an idea to showcase Ukrainian culture to the world. Petliura hoped that if the world saw how different it was from Russian culture, it could finally support Ukraine’s independence. He believed that music was the universal language that speaks to the heart of every person.

The idea was to bring the Ukrainian choir to Paris by the start of the Paris Peace Conference, where the future of Ukraine would be decided by the world’s powers. The choir was organized within a few weeks, and a huge budget was allocated to bring this idea to life. Oleksandr Koshyts, the friend and supporter of Mykola Leontovych’s work, was assigned as the head of the choir. When he asked Leontovych’s permission to include Shchedryk in the program, Leontovych refused. He said that he couldn’t imagine people in Prague or Paris being interested in listening to Shchedryk. Koshyts included the song anyway, and it became a world hit. However, Mykola Leontovych had never found out about the song’s success.

***

Two weeks after the choir’s tour preparations started, Russian Bolsheviks made a breakthrough and occupied Kyiv. The choir members stayed in the city until the very last moment when they were ordered to evacuate. Their mission was to bring Ukrainian culture to the world, and it would have been a disaster if they were captured by the Russians. The Paris Peace Conference had already started, and they didn’t have much time.

The singers managed to get into the last train, leaving Kyiv to Kamianets'-Podilskyi, where the capital of Ukraine was moved. It was February, the train didn’t have heating, and all the windows were broken. The rails were covered in snow, and the train made frequent stops that lasted for hours until the snow was removed. The journey that was supposed to last one day took almost a week, and people were starving and exhausted. At some point, the train crashed into a big pile of snow and went off the rails. Many were injured, but luckily, the choir members remained unharmed. Eventually, they reached Kamianets'-Podilskyi, where more singers joined the choir. After months of preparations and a wait for the papers, they left for Uzhhorod – the first town on their tour. It is a Ukrainian town, but back then, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

When the Ukrainian choir arrived in Uzhhorod, they were met by the police and put in jail. It turned out that Russians contacted the authorities and said that Ukrainian singers were communists to prevent them from performing. Locked in cells, Ukrainians were lectured by the head of the police about the great Russian culture and how there was no Ukraine. The choir was freed after the call from Ukrainian officials, and they gave their first concert, which was a tremendous success.

After that, the singers went to Prague, where the police detained them again. Russian informed Prague authorities that Ukrainians were smugglers who brought counterfeit money to Czechoslovakia. The police confiscated all the money from the choir members without any investigation. The singers recalled in their diaries that they were met with big hostility and that every encounter ended with Ukrainians trying to persuade people that Ukraine existed and was an independent country. The concert was held on May 11, 1919, and the Czech people immediately changed their attitude. They completely fell in love with Ukrainian songs and culture. Shchedryk became a hit that people sang on the streets.

Professor Zdeněk Nejedlý of Charles University said after the concert:

“So, gentlemen, who need 20 lines of music to express their worthless thoughts, try to do it in four lines, like Ukrainian composers!”

Czech conductor Jaroslav Kržička, in his review for Hudebni Revue, wrote:

“It is difficult for my hand to write criticism when the heart sings praise. The Ukrainians came and won. I think we knew very little about them and deeply offended them by unknowingly and uninformed lumped them together against their will with the Russian people. Our desire for a ‘great and indivisible Russia’ is a weak argument against the distinct nature of the Ukrainian people, for whom independence is as vital as it once was for us.”

Despite multiple attempts and hard efforts, the French visas for Ukrainians were constantly denied. French authorities viewed Ukraine as an unrecognized state, and Russian emigres used all their influence to prevent Ukrainians from coming to Paris. The Peace Conference was in full swing, but Ukrainians could not enter France. They had no choice but to tour other European countries.

After Prague, the Ukrainian choir moved to Austria and performed 11 concerts there. The Austrian press wrote:

“Ukraine’s cultural maturity must become the legitimization of its political independence in the world.”

Then the choir moved to Switzerland, where it also had a huge success. A correspondent for the Swiss newspaper La Patrie Suisse wrote:

“The Ukrainian Republic is striving to restore its independence and decided to demonstrate that it really exists. ‘I sing, therefore I exist,’ it says. And it sings amazingly.”

***

While Ukrainians were captivating the hearts of people with their songs all over Europe, the fate of Ukraine was already decided in Paris without them. It seemed that they would never make it to France until one day, the French ambassador attended a Ukrainian choir’s concert in Bern. He was so moved by Ukrainian music that he wrote a letter to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs asking to grant visas to the choir members.

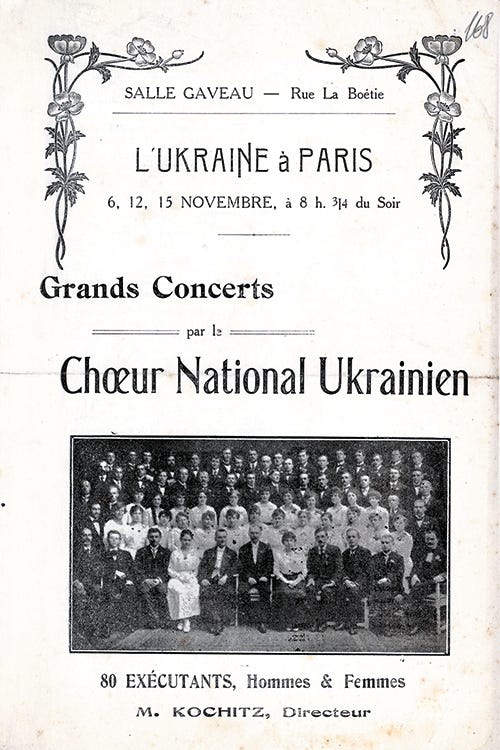

The choir was finally able to come to Paris in November 1919, nine months after they left Ukraine. By then, the world’s leaders had already decided to divide Ukraine between Russia, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. The choir came too late.

On November 6, 1919, Ukrainians performed in Paris. Russian emigres gathered by the theater and tried to disrupt the concert by booing and declaring the choir members the enemies of France until they were escorted by the French police.

Ukrainians, whose hearts bled for their country, went on stage with the words: “We who are about to die, salute you.” The concert in Paris was a colossal success. Shchedryk was asked for an encore again and again.

The Ukrainian choir gave 25 concerts in France. Georges Guiraud, a professor at the Toulouse Conservatory, wrote:

“They said that Ukraine is a part of Russia. Why did the Russian government hide Ukrainian music from Europeans?”

He noted:

“We know the names of famous Russian composers: Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, but there was never any mention of Ukrainian composers. Why has this school of music not been known to us until now? Was it destroyed by the weight of the glory of the great Russian colleagues?”

While the French audience admired Shchedryk and wrote praise, Mykola Leontivych had no idea his work was successful. He was surviving in poverty and hunger under the Russian occupation.

After France, the choir performed more than 100 concerts in Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, and Poland. The concerts were attended by heads of state, royal families, famous academics, and celebrities and always received the highest praise. The choir was also supposed to perform in Italy, but their visas were revoked the next day they received them due to Russian never-ending interference.

No matter where the choir went, Shchedryk captivated people's hearts. It became especially popular in the Netherlands. The song was translated into European languages, and for several months, Shchedryk played from every house in Europe.

Franz Hellens, the future four-time Nobel Prize nominee for literature, wrote:

“Thanks to folk poetry, Ukraine is revealed as one of the most picturesque nations of Eastern Europe.”

Brussels newspapers wrote:

“Ukrainians have given us not only beauty but also a lesson in national self-awareness.”

The idea of Symon Petliura worked, the entire Europe was captivated by Ukrainian culture and resilience. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough to save Ukraine. By 1921, Russian Bolsheviks completely occupied Ukraine, and they started to arrest and kill Ukrainian composers, musicians, writers, artists, scientists, and politicians.

***

In January 1921, the Ukrainian choir started a new tour in Paris. The concerts were attended by well-known composers, music critics, General Maurice Pelle, ballerina Isadora Duncan, and others. “Tuxedos, costumes from Palen and Wort. Perfumes and diamonds from the Rue de la Paix… Limousines and Rolls-Royce cars with livery-clad drivers and often crowns on their hats were in front of the theatre door,” that's how it was described in the papers.

Mykola Leontovych has been called “the Homer of music,” and Oleksandr Koshyts “one of the best choral conductors in Europe.”

On January 23, 1921, the choir gave the final morning concert, where Shchedryk was met with encores as usual. Little did they know that at the very same time, Mykola Leontovych was killed in his home by a Russian agent, Afanasy Hrishchenko. He came to the house the evening before, pretending to be a lost traveler, and asked to spend the night. Leonotvych's family let him in, shared a dinner with him, and went to sleep. In the morning, the family woke up from the sound of the shot. The agent killed the author of the most loved song in Europe, robbed the house, and fled. No one in Paris knew about it, and the press continued to praise Mykola Leontovych, who never found out about the success of his work.

***

In 1922, the Soviet Union was formed, which swallowed not only Ukraine but all the neighboring countries. The Ukrainian choir did what they could, but despite the enormous success of Ukrainian music and culture, the world’s leaders didn’t want to recognize the independence of Ukraine. The members of the choir didn’t have a country to return to anymore, and they left for the U.S. Only one person later came back to the Soviet-occupied Ukraine, was immediately arrested, and shot. All the other singers never returned home and had no contact with their families.

The Ukrainian choir gave its first concert in the U.S. on October 5, 1922, at Carnegie Hall in New York. Like Europeans, the American audience was mesmerized and impressed by Ukrainian music and completely fell in love with Shchedryk. The choir toured across the U.S. and received standing ovations everywhere they performed.

Unfortunately, the person who organized the concerts of the Ukrainian choir in the U.S. was an immigrant from the Russian Empire who loved the idea of great Russian culture and incorporated Russian singers into the program. The choir members had no choice, as they relied on him and his help with their promotion. Because of that, many American newspapers started to call the Ukrainian choir “a Russian choir” and labeled Shchedryk “a Russian folk song.” They also called Mykola Leontovych a Russian composer, despite the fact that Russians killed him for being a Ukrainian.

The singers were outraged and shocked. Leonid Troitsky, the choir's tenor, said in an interview with The Dallas Morning News:

“Your newspapers call us Russians, but they are wrong. We are Ukrainians, even though the Soviets rule our country.”

Ukrainians continued to emphasize that they were Ukrainians and that Ukraine was an independent and different country from Russia, with its own culture and history in every interview.

“We didn’t even expect that they [Ukrainians] had a thorough knowledge of art,”

wrote the American newspaper St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

“If someone sings only with their voice, these people sing with their history,”

wrote The Pittsburgh Post.

From 1923 to 1924, the Ukrainian choir performed in 115 cities in 36 states of the U.S., as well as in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cuba. People were deeply moved and impressed by Ukrainian culture everywhere, and Shchedryk was called for encores.

While Soviet Russians did everything to erase Ukrainian culture and crush Ukrainians in Ukraine, Russians in the U.S. did everything to steal the success of the Ukrainian choir and appropriate their songs and achievements. In 1925, a Russian choir in New York incorporated the songs that Ukrainians performed at concerts in the U.S. in their program. Russians sang Ukrainian songs to Americans and told them that they were Russian. Moreover, a Broadway musical about the Russian Revolution of 1917 played Shchedryk and other Ukrainian songs and referred to them as Russian songs, too. Russians just couldn’t leave Ukrainians alone, no matter where they went.

***

In 1936, the American conductor of Ukrainian descent, Peter Wilhousky, wrote the English lyrics and created “Carol of the Bells.” He heard Shchedryk at the concert and wanted to popularize the English version of it among Americans. The song played on American radio NBC and instantly became a hit. Since then, it’s been featured in popular movies and commercials and has become the world’s most famous Christmas song.

At the same time, Ukrainians, who were isolated and locked for 70 years in the Soviet dictatorship, had no idea about Shchedryk and that the entire world sang a Ukrainian song every Christmas. They found out only in the 90s, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and Ukrainians watched the American movie “Home Alone.” That’s how Shchedryk came back to Ukraine. When the archives were unlocked, Ukrainians learned about the genius of Mykola Leontovych and how the Ukrainian choir went on a mission to save their country by sharing Ukrainian culture with the world.

Right now, Pokrovsk, the town where the most famous Christmas song was written, is being encircled and bombarded by Russians. It’s been more than 100 years. Ukraine’s struggle for independence continues. The bloodthirstiness of Russians and the biases of the Western world haven’t changed either. Ukrainians still have to prove that they exist and are worthy of freedom.

It’s almost Christmas, and Shchedryk is playing on every radio and TV across the world. By listening to it, I want you to remember the story of incredible talent, resilience, and sacrifice behind this song. For a hundred years, Ukrainians have been sending the message to the world: “I sing, therefore I exist.”

The most popular performances of Shchedryk:

The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square

NBA players create Shchedryk melody by bouncing basketballs

Ukrainians sing Shchedryk in Lviv airport

Email: daryazorka@substack.com

Shop my art on Etsy

Watch the “20 Days in Mariupol” documentary

Watch Frontline PBS documentaries on Ukraine

Donate to help Ukraine: UKRAINE DONATION GUIDE

Gift a subscription to From My Heart ♥︎

"They also called Mykola Leontovych a Russian composer, despite the fact that Russians killed him for being a Ukrainian."

And this sentence alone is the epitome of russia, over and over and over again. What they cannot destroy in whole or in part, they claim as their own, and the world eagerly and readily believes it, even as our continued fight for existence proves otherwise. Even as I recognize the same struggles played over and over again today, I did not know Shchedryk was written in Pokrovsk, and every new realization is a stab in a heart I didn't know had enough flesh left for new wounds.

Thank you for this piece, Darya. I have heard various histories of this song many times before, but the strength in your voice and in your writing is in the simple humanity of every single story. Stories others would relegate to the dry definition of "history", something to be studied and not something that was, and continues to be, lived. It's easier to dismiss something as "history", when you don't need to take accountability for living in it now. The daily individual and collective hardships, courage, loss, love. Always I wonder what my family's stories are, but because of russia, I do not even know their names - and it's preserving each and every story you can, like you continue to do, that proves "I sing, therefore I exist".

This was beautiful and heartbreaking. I wept.